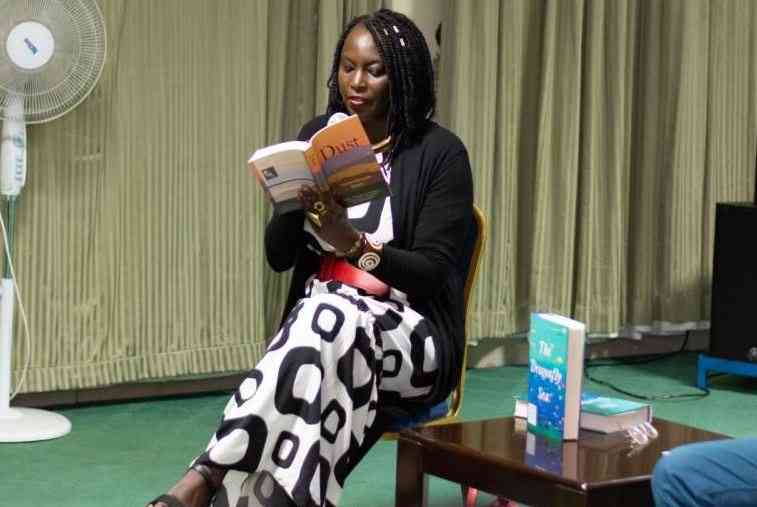

Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor is a woman of (among many other things) agreeable contradictions. Standing at about 5’9, she is a tall, but not towering frame and oozes charm, good breeding and affable manners.

When she speaks, she looks gently into the eyes of whoever she is speaking to, and when she is spoken to, she will lean in to listen. When I met her she had a book reading courtesy of a cultural exchange programme by German UNESCO called Tandem. As part of the programme, we (about 60 participants from Kenya, Ghana, Togo, Namibia, Cameroon and Germany) are in a seminar in Nairobi for a month before we move to Germany where we will be placed in different cities and institutions to come up with and implement projects.

The first thing Yvonne said in introduction was that she is politically incorrect. This was interesting because we have spent the last three weeks in Nairobi trying to be politically correct – decolonising spaces, phrases (turns out the phrase ‘when you go black you never go back’ is quite racist and needs decolonising) and histories.

Years ago, before Yvonne was a successful, politically incorrect writer, she was a corporate cow, an amazing one. She could have ended up as a Senior Development Officer in a big NGO/ORG had she not walked out of an office job to pursue her artistic calling. Her first story, Weight of Whispers won the Caine Prize in 2003. The story, she says, was written in five days, and she wrote it just to get the late Binyavanga Wainana off her back.

When she speaks of Binyavanga, there is a transformation in her demeanour, from the cool, laughy Yvonne to a much gentler one – something I have noticed in a lot of the older authors who interacted with Binyavanga in his prime and in the Kwani? era. Even in the most gangster of them, like Tony Mochama, a current official AU (African Union) Writer-in-Residence. I do not think Binyavanga inspired gentleness – quite the contrary – he was a loud, merry man.

However, it might be because every one of these authors recognises not only his contributions to the Kenyan literary scene but also what he did to their personal lives – the unsolicited but very welcome literary ‘Godfather’ that he was to almost all of them. Her greatest lesson from him was to get out of the way of stories. It would take her another seven years after Weight of Whispers to finish Dust, which was inspired by the post-election violence (PEV) after the 2007 General Election results were disputed. However, the first version of it was done during the Orange-Banana referendum in 2005.

“I remember wandering through town and having this overwhelming sense of terror. I remember thinking: they are going to tear this country down. And they did,” she says.

While the country was burning, she took a bus down to Eldoret in the company of seven other writers to collect stories. At one of the churches where some of the survivors were being sheltered, she remembers seeing an 80-something-year-old woman, sitting alone, in silence, having lost everything, her only possessions left being mismatched bathroom slippers and a kitten. From this image, Dust emerged.

A lot of things have been said of Dust. Eric Rugara describes Yvonne’s writing in Dust as “an ancient storyteller, in a high poetic tone, like music made for ears not mortal. What Cormac McCarthy does, when he drifts into ancient-sounding poetry, she sustains for an entire book.” I love the book for (among so many other qualities) its short sentences, which I had initially thought had to do with Binyavanga (who himself was a king of short sentences) but it turns out, it had nothing much to do with Binyavanga’s style. To Yvonne, Dust is simply a protest against the Language of Silence that we as Kenyans have “collectively mastered and are fluent in.”

Her latest novel, The Dragonfly Sea, was inspired by the stories of the generations of Chinese descendants from hundreds of years ago when a ship carrying Chinese sailors capsized off the Indian Ocean near Siyu in Lamu and some of the sailors were trapped and settled in the island. More than 600 years later, a young girl, Mwamaka Sharifu was sent to China as an emissary of those hundreds of years of history. I found out (from my roommate in the programme – a gentle, bubbly girl from Germany, and a Tolkienist herself) that Yvonne is also a huge fan of Tolkien. She talks about J.R.R Tolkien in the bubbly, out-of-breath way that is sometimes common with fan girls. At that moment, Yvonne the fan girl takes over from the collector-of-stories Yvonne, and she is suddenly in The Shire, talking Elven and doing whatever Middle-Earthers do.

“I admire his capacity to build worlds. He is a genius in languages. Just imagine it, Elven is a living language! I love that he can look at the abyss, at the darkest things of human doing and still find a way to bring light.”

She maintains she belongs to the school of literary agnosticism and her loyalty is only to the story. For her, the strangeness of her Muse is that it is jealous, and she cannot write when she is attached to something else.

Related Topics